It is said that since the days of Christ, the foot soldier has fought with 60 pounds of battle gear. Let’s talk “battle rattle” by looking at it in various forms, keeping in mind that each variation is designed to aid the modern warrior carrying and using a range of battlefield operating systems.

First we need to dispel with the myth that there will be a one-size-fits-all solution for battle gear. That’s simply not practical. Warriors carry a variety of weapons, from rifles to carbines to crew served machineguns, rockets and mortars. They carry various radios, night vision devices, medical equipment, plus breaching tools and explosives. This equipment requires specialized carrying gear.

Furthermore we have to consider the battle environment as well as how the warrior entered the battlespace. Mechanized and motorized infantry battle gear may look very different from airborne and air assault forces. And mountain warfare battle gear may look significantly different than urban warfare or jungle warfare equipment.

That being said, the US military has for the past 100 years projected itself across the globe in every conceivable battle environment. As such, there is an understandable effort to develop a system that effectively manages various demands on our Armed Forces.

This requirement for flexible, modular battle gear is not necessarily a requirement for all forces. Troops who are dedicated to a given geographic and environmental fight – such as the Alabama Home Guard or the Israeli Army – may not agree that battle gear needs to be so flexible. That is understandable.

So again, let’s be careful to avoid a “silver bullet” solution when we think about battle rattle.

Soviet BCP

In it’s simplest form, a warrior needs to carry his weapon, ammunition, and water. Two hands and a bandolier manage most of this.

An advancement over this hodge-podge system was the Bandolier Chest Pouch (BCP), first introduced by Soviet forces toward the end of the Second World War to accommodate for various weapons using “box” or “stick” detachable magazines. And since virtually all modern weapons use detachable magazines today, the BCP is still a relevant form of battle rattle.

The advantages of the BCP are its simplicity and affordability. It is used extensively by communist militaries throughout the world, and more recently has been introduced to the United States as viable battle gear. The BCP does what it was intended to do – carry ammunition.

Of course the limit of the BCP is also its disadvantage. It does not carry much else. And when beefed up versions of the BCP came out, they were so hopelessly front heavy and bulky that these variations were useless to everyone except those motorized troops who’s mission dictated that they would remain seated until the very moment before engagement, and even then it was only really suited for urban warfare. Troops certainly couldn’t crawl around in the dirt or comfortably hike up mountains with this large, unevenly distributed BCP.

Another disadvantage of the BCP is that it is not particularly easy to get in or out of this equipment. Straps go over the head, cross at the back of the shoulders, and another strap circles completely around the midsection. That can prove disastrous in the event a troop fell into deep water, or a wounded casualty had to be stripped to get to the wound.

The very recent introduction of PALS webbing, heavy duty nylon strips sewn onto various strap and pouch surfaces, attempts to address the shortcoming of modularity for the BCP. While small additions are appreciated on the shoulder straps and front of magazine pouches, as previously noted the weakness of the design rests with the unevenly distributed weight of the BCP.

Further recent additions of quickly detachable buckles make the BCP easier to get on and off. However, with between three and six buckles to hit in sequence, the warrior could still drown or bleed to death before the BCP was removed!

These shortcomings recognized, the BCP is still a decent choice for battle gear. It is affordable, simple, and with recent advancements it is a comfortable piece of gear. Coupled with a modern hydration bladder, the BCP is a streamlined, lightweight, minimal approach to battle rattle.

Commonwealth Army Kit

The British Army introduced what may be the first modern effort to modularity for various warriors and their weapon systems by the Second World War. This effort sees considerable improvement in the now-famous 1958 Pattern webbing, called “kit” and “web gear” by warriors literally around the world. It was copied by various militaries throughout NATO, as well as carried by common wealth armies in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and South Africa. Influence of the ’58 Pattern webbing can still be seen today in the militaries of North Africa, the Mideast, and the Indian subcontinent.

Sturdy and comfortable, the British kit could carry various types of equipment. Yet it also had a significant disadvantage in that trying to be all things to everyone, British kit “fit everything, but fit nothing well.”

Since then the British have upgraded their kit multiple times, including the current Personal Load Carrying Equipment (PLCE) webbing introduced in 1988. PLCE is heavy duty nylon webbing rather than the old canvas webbing. Notably it includes pouches, scabbards and holsters tailored to specific gear while maintaining its modularity and a reasonable distribution of weight.

The downside is that as British kit advanced in its capabilities, it became more expensive and harder to find! When you can find British PLCE outside of the UK, you will pay a kidney for it. Yet it is incredibly formidable battle gear.

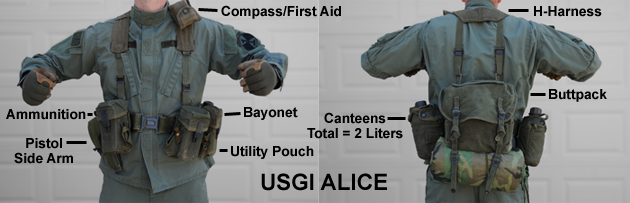

ALICE LBE

About that same time the Americans also enter the fray in earnest with the canvas M1956 and subsequent nylon M1967 All-purpose Lightweight Individual Carrying Equipment (ALICE), a.k.a. Load Bearing Equipment (LBE). The LBE is a modular approach to battle rattle.

Like the British counterparts’ kit, the LBE pistol waist belt and shoulder straps are adjustable to fit a wide range of warrior sizes and heights. Unlike the British kit, though, the American LBE was suited to specific equipment and weapon systems from its very start.

LBE has the advantage of being an open system, that is, the straps make it a rather cool system for carrying equipment. When on parade LBE straps are tightened and the pistol belt fastened, lending to a very sharp uniformed appearance in the tradition of Roman Legionnaires. When going into battle, the LBE straps are lengthened and the pistol belt is often left unfastened or significantly extended. This lowers the ammunition pouches to below the hips, giving the LBE a bit of a “gunfighter” appearance. The modularity becomes a personalized to fit each warrior, and the entire rifle company takes on the look of helmeted cowboys.

Here in the United States, anyway, the LBE is readily available in both generations and is incredibly affordable. It never fit well around body armor, however, and because of this many US Soldiers and Marines found it somewhat uncomfortable to use with body armor.

LBV-88

Now there are those who insist senior US leaders couldn’t stand the “wild cowboy” image of US troops with unfastened pistol belts and low slung pouches. Individuality is an affront to the sensibilities of such armchair warriors.

Still others insist it was simply the LBE’s lack of design considerations for body armor, and the prevalent use of body armor that sent the designers back to the drawing boards 30 years later.zWhatever the case, the result was the M1988 Load Bearing Vest (LBV). The LBV-88 departed from the modularity concept of ALICE, though to be certain LBV used the ALICE pistol belt and many of the pouches, notably 1-quart canteens continued to be used with the LBV-88.

From the onset the LBV was a welcome piece of gear. It maintained its fit of a wide variety of troop sizes and wore more comfortably over body armor, as designed. Furthermore, with the magazine pouches up higher on the chest, the LBV harkened back to the BCP concept – but with a much nicer distribution of load weight, some modularity, and the ability to get the LBV on and off with the click of just two front buckles. Not a bad design at all.

Still, the LBV-88 was a dedicated vest. It didn’t suit machine gunners, grenadiers, radiomen, mortar men or medics very well. It needed greater modularity. It saw only 12 years of service.

Tactical Vest & Camelbak

Recognizing this shortcoming, Eagle Industries in the United States championed the TAC-V1 series vests – though clearly there are far too many competing manufacturers to note in this space. The TAC-V1 series vest attempted to do for every warrior what the LBV-88 had done for the rifleman. TAC vests tailor a specific, dedicated piece of battle gear to each warrior’s needs.

The idea was pretty sound. And certainly the uniform (non-modular) appearance of the TAC vests would get a nod of approval from those leaders concerned with a stylishly clean look on the parade grounds. However the expense and logistics of the TAC vests very quickly became a major headache!

TAC vests aren’t as adjustable as their earlier predecessors. There is a separate vest issued for warriors of tall, regular and short heights. This is true as well for large and small girthed warriors such as one might expect in the difference between a 40-year-old, 220-pound male warrior and a 18-year-old, 115-pound female warrior. And for those warriors who were in the middle range of sizes, they might very well need two TAC vests – one worn with body armor, one worn without.

And what if a machine gunner in the platoon was reassigned as a grenadier? There is no guarantee that they’d fit the same vests. So the idea of simply swapping battle rattle wasn’t going to work. Obviously a new vest must be issued for the new job. There is little modularity with the TAC vests because the pouch configuration is sewn permanently into each vest.

Additionally, the troops complain that TAC vests are too hot and that any serious physical exertion quickly causes overheating. Though comfortable and sturdy, TAC vests simply don’t ventilate well in hot climates.

Understandably the US Army, Marine Corps and Air Force adopted the TAC-V1 only on a very limited basis, almost exclusively issued to special purpose military police and security police. The TAC vest has seen greater success with civilian police departments, in particular with SWAT because specialization is precisely their requirement.

Yet an interesting and wildly successful development did come from the TAC-V1 series battle gear, and that was the introduction of the back-mounted hydration bladder, tube and valve. This item is commercially recognized by the name Camelbak, though again today there are numerous manufacturers of this fantastic yet simple evolution in canteen technology.

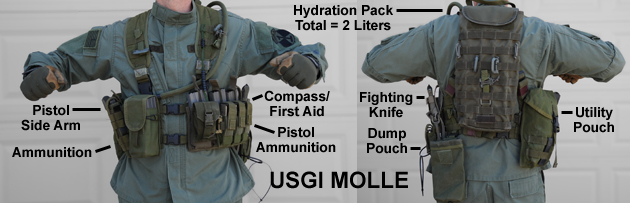

MOLLE

Modular Lightweight Load-carrying Equipment (MOLLE), pronounced “Molly”, replaces the older generation of “Alice”. American troops have a history of naming their equipment after women, and understandable fascination for healthy young males. Commonwealth forces are also using a variation of MOLLE called the Osprey modular system.

The MOLLE system incorporates an ample use of PALS webbing throughout, making this battle gear extremely modular and flexible for a variety of warrior missions as well as warrior sizes. Even the body armor and rucksack employ PALS so that pouches and equipment can be directly attached.

The Marines call this MOLLE system the Improved Load Bearing Equipment (ILBE) while Soldiers simply call it MOLLE. Though different names, both the US Army and Marine Corps use two-piece vest panels, known commercially as the Modular Assault Vest (MAV).

The MAV also comes in a one-piece panel configuration that offers more room for equipment, but this variation is less popular because it suffers the same design flaws as the BCP. Namely that would be a somewhat unequal distribution of the load weight to the front, and difficulty in getting the battle gear on and off quickly.

Still, the two-piece MOLLE MAV gear has been in service for a decade now and appears well liked by troops of various nationalities who’ve used MOLLE in the deserts and cities of Iraq, and the mountains of Afghanistan. It is robust, modular, allows for excellent distribution of weight and specialization to each warriors role in the mission. And the MOLLE MAV fits a wide range of warrior sizes, both with and without body armor.

The single criticism of the MOLLE MAV so far is that it is apparently designed for use with body armor, and some complain that it is difficult to lower the warrior’s profile and crawl on the ground. Still, the MOLLE MAV is modular enough to handle this by simply adjusting more equipment to the sides of the vest panels and back of the hydration bladder pouch. And MOLLE gear is considerably less hot than the earlier TAC vest variations!

Does it look good on the parade ground? No, not surprisingly. Wearing the MOLLE MAV the warrior assumes something akin to a potato shape. It is relatively comfortable, but the tradeoff is that because the modularity allows each warrior to custom fit their ammunition and equipment management, no two MOLLE MAV set ups are identical.

Surely as combat patrols fade in frequency, more an more senior officers and NCOs will insist that the MOLLE MAV stop doing what it does best – being fantastically modular.

This article was originally published on odjournal.com (Olive Drab: the journal of tactics) and has been transferred here with permission.

Pingback: Scaleable Load Carry – The Milsim Perspective